Welcome to all the new subscribers! I’m so glad you’re here. If you’re a free subscriber and you haven’t taken advantage of the spring sale yet, now is the time! 20% off of annual subscriptions for first-time subscribers continues until the end of the month.

If you’re a free subscriber, you might want to consider joining the paid community so you can take advantage of things like today’s cookbook giveaway. There will be a few more of these in the coming weeks as we celebrate spring cookbook season, and they are only open to paid subscribers. Plus, you’ll get a new recipe every week, as well as full access to my archive of recipes going back FOUR years—that’s almost 300 recipes. I work hard to bring you this newsletter week in and week out, and it would not be possible without your support, which I am so grateful for.

On to today’s newsletter. Lots of new cookbooks have come across my desk in recent weeks, but this one immediately caught my attention. Not only because it was written by Lucinda Scala Quinn, who I hired to work at Martha Stewart Living towards the end of my tenure there, but because I love this kind of food. I love it even more now that I’ve learned more about the origins of so many dishes that have become typical Italian-American fare—dishes I previously might’ve taken for granted.

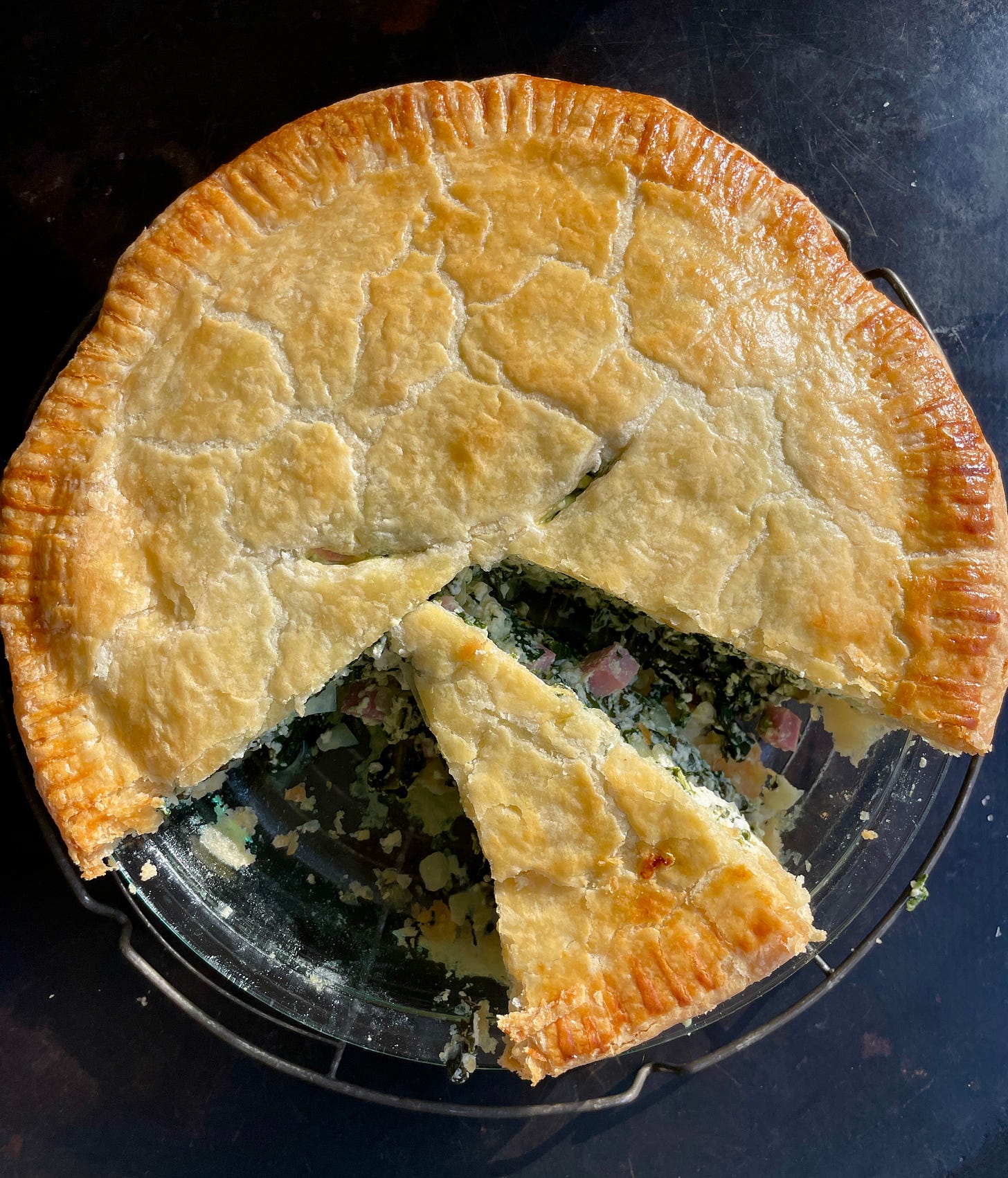

While I don’t personally celebrate Easter, I’m sure many of you do! So I figured I’d feature Lucinda’s recipe for Savory Easter Pie (or Torta Pasqualina, which is so much more fun to say). I gave this a trial run yesterday, as I always do when I excerpt a recipe. It was really delicious, and the perfect thing to make ahead for a busy holiday.

We have lots of greens already in the farmers’ market, but I used a combination of chard, baby spinach, and dandelion greens from the supermarket, plus some cute little over-wintered collards I got at the Union Square Greenmarket last week. You can use any combo of greens you like here.

To win a copy of Lucinda’s book, simply comment on today’s post, and I’ll choose a winner at random on Monday, April 21st. I’ll notify you by DM and email, so keep an eye on your inbox! You must be a paid subscriber and a U.S. resident age 18 or over to enter. See the bottom of this post for the giveaway fine print1 and click the button below to leave your note.

A Conversation With Lucinda Scala Quinn

SUSAN SPUNGEN: This book is clearly very personal to you. Why did you want to write a book about Italian-American food?

LUCINDA SCALA QUINN: This is a different kind of Italian American cookbook because what I saw growing up (back in the day) was an army of women; my grandmother, her sisters, sisters-in-law, and all the other women in the family doing all the shopping, cooking, cleaning and serving. Yet, over the years, as a member of the professional culinary world it seemed as though the foodway was represented through the men; restaurants called Patsy’s, Gino’s, Rao’s, and in films like the Godfather aesthetic.

So-called “mamma” or “nonna” was an ideal of the smiling big-hearted Nonna ready to feed everyone effortlessly. The reality was much different. They were the founders of a whole new type of Italian-influenced cooking, created under tremendous duress, which I outline in detail in the book. In fact the stove, the kitchen, and dining table were their only creative power centers over which they ruled.

Today, often a young male chef will give a nod to their grandmother's Sunday dinner, but rarely have they been credited with creating a whole original, frugal foodway out of necessity, which today, 100 years later, is considered a favorite American food. I wanted their story told, since I knew it first hand in my own family, and my research revealed how omnipresent it was in every other immigrant southern Italian family who fled the Mezzogiorno during the great migration.

SS: How would you say Italian food evolved once it (and the cooks who made it) reached the U.S., becoming a cuisine unto itself?

LSQ: The immigrant southern Italians arriving in the USA between the 1870’s and 1930’s practiced what is known as cucina povera (the cooking of the poor). It is a way of eating, prevalent in every province/district/century in Italy, where homegrown produce, fresh or preserved, or affordable ones such as grains, beans, offal, and bread heels are used and reused into imaginative concoctions. These frugal methods arrived in an America not only filled with an abundance of meat, fish, and produce, but also at the dawn of a new canning, frozen food, and ground meat industrializing American food system. Meat, eaten rarely or in processed salumi in the old country, was suddenly abundant and affordable. Where old-school techniques merged with this newfound bounty and the heretofore immigrants known as Calabrese, Pugliese, Sicilian, etc. generalized into “Italian,” well... a whole new foodway was born, and found its own evolution from family to family, which continues to this day.

SS: Lots of people have a soft spot for this kind of food after growing up eating in “red sauce joints.” Tell us how this cuisine (and your book) is much more than just red sauce.

LSQ: As I mentioned, vegetables, beans, and grains play a huge role in this food, and they are all prepared in a multitude of ways, either as the star, or as a compliment to a red-sauce dish, or other main meal such as Chicken Marsala or Roasted Lamb. Also, as Italians intermarried with different ethnicities, new takes on recipes emerged, like the Meatball Sandwiches reimagined by my non-Italian mom, or the Lemon Spaghetti that I created for my mom who, I learned later in life, was not a fan of red-sauce in spite of cooking it all the time, like any Italian wife back then was expected to do. Antipasto platters, so prized today for snacking meals and always a part of our family eating, have many pickled, baked, and preserved items without any red sauce at all.

SS: Being thrifty and resourceful is typical of Italian cooks, and has become a popular concept in recent years. I’m reminded of this every time I rinse out a can of tomatoes with water so as not to waste a drop. Can you talk a little about frugality, and how it is so central to this kind of cooking? What are some of your favorite ways to be thrifty?

LSQ: Well. I too always rinse out my can of tomatoes with a little water. I don’t buy wasteful, expensive tubes of tomato paste, but rather cans. I dollop tablespoon blobs of the remaining paste in the can and freeze them for easy access on future occasions. I make breadcrumbs from collected bread heels, saved until I have enough to make a pint or quart of crumbs. Then, I flavor as needed, and brown to use as a crunchy cheese-alternative topping, especially when serving seafood dishes already rich in umami flavor. Every time I peel a carrot or celery or strip leaves from a parsley stock, peel onion or garlic, I save all those bits that might be thrown away and collect them in a resealable freezer container. Once a week, I make vegetable broth for soups and sauces. I always buy whole birds, break them down myself, and make broth from the back, wing-tips, and other bones, while the parts are tailored to a recipe. I collect and use clean soaking liquids such as from dry mushrooms, tomatoes, or beans to flavor and stretch other recipes. All of these practices were ingrained in me by my grandmother, her sisters, and my mother. Not as deprivation, but innovation and expansion.

SS: Readers might like to know that we worked together at Martha Stewart Living for several years. I think it’s safe to say that we both learned a lot there, and I know for me, one of the biggest things I learned from Martha herself was to always be curious. I always have been, and I imagine you have too. How did your curiosity help you connect with the women in your family, and inspire you to tell their story?

LSQ: As a student at an experimental college in its heyday (Hampshire College in Amherst, Mass.), we created our own curriculum, especially our senior thesis. My Italian grandmother had recently died and all her sisters and family still lived in Rome, NY, where their mother had immigrated to from Calabria in Italy. I sensed there was a lot to learn from them, all then in their 80s and 90s, and I was curious about the story of these strong women in my family, especially as I was the only girl in mine with 3 brothers.

I was a film/photo student, so I made an exhibit which included 16x20 color hand-made photographs and written transcriptions of interviews. I visited multiple times over a couple years. My instincts paid off because soon after that, a whole way of life would be gone.

That project was unearthed 40 years later, after I’d already written 3 books about raising sons. I felt it was time to turn my attention to the amazing women in my family, including my mother, who were so influential in shaping my mindset and career. Too many women haven’t had their story told. Now I think we are living in a golden age of learning more about the history of our pioneering female foremothers, but also what the fruits of their labor have manifested in so many young women today telling new stories of bravery and change.

SS: Tell us a little bit about today’s recipe, the Torta Pasqualina, and what you would serve with it to round out an Easter menu.

LSQ: This was the first “pie” I ever learned to make, and we made it at my first professional cooking job when I was 16 years old. We served it at lunch as wedge on the plate nestled next to a crispy green salad tossed in vinaigrette. I loved the contrast between the hot, salty, flaky crust enrobing the cheesy soft spinach filling and the cold, tangy, crunchy lettuce.

For an Easter lunch, I’d make a salad, like the Fennel and Orange Salad, and on the side, Steamed Asparagus with Tarallucci Lemon Cookies and Sherbet-Stuffed Frozen Lemons for dessert. Or, as a part of a larger Easter dinner, I will make Brother Jim’s Easter Lamb, and serve it as a side along with the asparagus and Baked Artichokes. Sometimes, I make savory hand-pies using the same filling and dough fashioned into individual portions.

SS: Lastly, and I know authors hate this question, because clearly you love all these recipes or you wouldn’t have included them, but what are some of your other favorite recipes from the book? Or, at least the ones you cook the most?

LSQ: Nothing could be more basic, but it’s my everyday, ride-or-die last-meal red sauce (Sugo) on page 63. Served with spaghetti, topped with grated Pecorino Romano cheese, a swirl of extra virgin olive oil, and a pinch of ground peperoncini. I eat it once or twice a week.

Savory Easter Pie

By Lucinda Scala Quinn